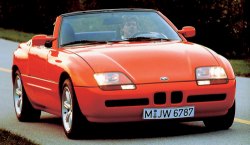

When I saw BMW Z1 from magazines in 1987, I was very excited. Think about it: a compact roadster measuring shorter than 4 meters, weighing just 1020 kg, powered by 325i's six-cylinder engine good for 171 hp, front-mid-engine design (yes, the whole engine was mounted behind the front axle), a new multi-link suspension, a pretty body made of plastic composites, a pair of pop-up electric doors that looked like coming from James Bond's cars…. Z1 was developed by the research department of BMW as an experimental project testing the latest aerodynamics, plastic body materials and suspensions. Why was it named "Z" ? there were two versions of the reason, one said Z stands for "Zunkuft" in German, meaning "future"; another version said the car was named after its Z-axle rear suspensions, which would be used in the next generation (E36) 3-series. No matter which version was correct, they no longer apply to the subsequent Z cars. Ridiculously, its successor Z3 returned to the old semi-trailing arm suspension of the E30 3-series in pursuit for lower cost, while the styling of the car was retro instead of futuristic. The Z1 had various features made it a BMW classic. First of all, its body and chassic structure was unique. Most convertibles at the time were troubled by two problems: poor aerodynamics and chassis rigidity. The Z1 solved both problems handsomely. It had a pretty good drag coefficient at 0.36 with the roof up and 0.43 when the roof is down, thanks to a smooth body and a flat composite undertray covering the bottom of the car. The undertray drew air towards the integral rear diffuser, which generated "ground effect" and sucked the car towards the ground. As a result, the Z1 ran stably at high speed yet without needing big spoilers. Nowadays diffusers have became very popular to high performance cars, but in 1988 it was a unique feature of the futuristic BMW roadster. The chassis of Z1 differed from other convertibles. It was by no means a conventional car with its tin roof chopped off. The steel monocoque had especially strong side sills to compensate the loss of roof. Furthermore, the composite undertray and the strong torque tube (linking between the transmission and the rear differential) also strengthened the chassis.

Now the high sills enabled an interesting feature - a pair of vertically raised doors. Let me quote an interesting description from Rowan Atkinson (Mr. Bean) here: "It has got doors that do not open. They simply disappear. You press a recessed button on the outside (it is very stiff, and a nightmare for anyone with nails), and the window and door sink down into the bodywork. You then clamber in over the high sill, (very difficult with a raised hood, and extrememly undignified for anyone with a skirt) and pull a handle on the inside. The door and window rise. It really is very impressive."   The Z1 had its cockpit located quite rear, allowing the 2.5-litre engine to sit amid-ship in front of the driver and achieving 50:50 balance. In addition to its sophisticated suspensions, it should handle very well. Yes, it did, but not as fun as predicted because it was overweight and underpowered. When the car entered showrooms in 1988, people found its kerb weight increased from the originally announced 1020 kg to 1250 kg. (To add salt on its wound, Autocar put it on the scale and measured 1338 kg) As a result, the Z1 was actually heavier and slower than a 325i. 0-60 mph took about 8 seconds, very disappointing. Moreover, the combination of civilized engine and grippy tires (225/45ZR16) meant the car handled securely rather than entertainingly. More problematic was its price - £37,000, or 3 times of a Mazda MX-5 ! this was seriously overpriced for a roadster offering so little performance. Not to mention the average build quality - the Z1 was not assembled by BMW itself, but by coachbuilder Bauer (the same as M1), which sourced a lot of cockpit components from aftermarket. After only 8,000 cars built, BMW pulled the plug on Z1. |